No.225

We have had freezing temperatures here in northern Scotland, and snow, the kind that you wait for without realising because any suggestion of seasons happening as they should eases the persistent anxiety of climate. The valley quietened, and having decided to hold our Christmas on the 17th and 18th of January—in the living room, as two people, one houseplant (the Araucaria heterophylla) designated as a tree—it felt like an odd, timely blessing that the mountains were now nestled down in their snow layers; I chose to believe that postponing any semblance of a festive feeling was the cosmically correct thing to do—the skies had agreed, I thought, and then opened their coldest corners.

We watched Casablanca by candlelight, I gifted you a Japanese knife, and you gave me a long-necked musical instrument of strings, found second-hand from someone in the town who owned two but only played one. I also trimmed your moustache out in the snow, and you somehow found the time to spend countless hours over the two days doing intense and beautiful meddling with the gas boiler. In a small hindsight, I wonder if you actually ever came to rest.

Someone said they heard people were skating on the iced-over loch up the hill, which I presumed a unsafe idea given that the water had only been provided with a week or so of ice growing, not freezing for months on end as in some places, the water only deciding very temporarily to harden itself against change. Not long after the loch you saw a bird in the white-covered heather that we couldn’t later identify with the Collins A Field Guide to the Birds of Britain and Europe. We play scrabble, you win.

I’ve gone through more Earl Grey tea that I know what to do with, in the same way that, having moved house over the turn of the year, I now don’t know what to do with the half-unpacked boxes of belongings, or everything needing to be in different places to before—fifteen nights here and I still can’t get my body to remember where the kettle is, or which counter space has the fridge underneath, or to step carefully over the sharp-edged inches that go between the hallway and the kitchen, the hallway and the bathroom. The small string of fairy lights we strung up in the Araucaria heterophylla come on at random times throughout the days following ‘Christmas’ but I do not bother to work out why, or to change this.

Moving house has felt like taking a long, furred animal that you usually only see from above, and placing it stomach-up, soft underfur showing the skin below, and needing to step a bit more carefully between decisions for fear of disturbing—disturbing anything. The underbelly of a stoat, or a pine marten. To disturb is to interfere with normal function, the late 13th century distourben meant to “break up the tranquility of”, disturbing coming directly from the Latin disturbare, to “throw into disorder”.

Things have surely been thrown into disorder: my own singular, domestic disorder and the painful, painful chaos that continues elsewhere in the world, where there is no snow, no time as it should be, no respite from a genocide. This afternoon I ate the final satsuma but neglected to count the segments prior to consumption, an act which often goes some small way to rounding off the thought-edges of the painful elsewhere, in the same way that I can rely on certain other smoothing techniques: folding laundry, watching the rookery of hundreds as the birds take to the sky at dawn and then dusk and then dawn, sitting like a stewing plum in the bath, noticing the light patches as they stroke the walls, the floorboards, the soft things. To think about the world and its ongoing pain is synonymous with needing ways to cope, and if one can find ways of coping then there is far more availability inside the nervous body to act.

14:28 — I get another Earl Grey tea; the sunset will be at 16:16 today but this doesn’t feel true, the full moon is in six days and I think to myself I should know more by that time and perhaps also have figured out why my glasses are perpetually smudged

It is more difficult to find delight in January than other months, and this was true always but now seems increasingly so. From Charles Baudelaire’s Intimate Journals, translated by Christopher Isherwood: “Today, 23rd of January, 1862, I have received a singular warning: I felt the wind of the wing of madness pass over me.”

I think about madness and read words by human rights professor Noura Erakat:

“Israel isn’t just breaking international law. It’s creating precedent and changing it to make this violence permissible. What happens to Palestinians matters for everyone, everywhere. It sets a precedent that means no where else in the globe is safe. What more do we need to act?”

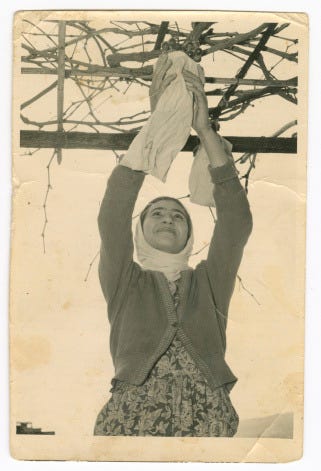

As the truth grows ever thicker, ice-like and impermeable, I think about all of the things that Palestinians should be doing, right now, instead: picking grapes, reading books, going on walks, running into the sea, sitting down to eat shared food, playing in streets and homes, singing to their infants, looking up at birds, sharing stories, writing histories, listening to music, watering plants, drying clothes in the sun. I could never make a list long enough, lists of verbs as long as the land Palestinians have always lived on, verbs that have been rendered impossible, verbs made completely unsafe, unavailable, verbs that come with a risk of death.

This morning, Friday, I pretend to make progress organising what was, until January 3rd, my office. Prior to this day at the before-house not one thing was boxed or wrapped, and everything had a place—crucially, a place I knew about. Now, everything (paints, papers, notebooks, sketches, letters, feathers, paperclips, brushes, ephemera that turned into permanence etc.) does have a place but those places are ones I did not plan for, seeing as all of it is chaotically but carefully spread out across both the floor and the desk.

It felt a necessary step, to take it first out of the cardboard boxes, but then most of it currently lacks a container or a drawer or a shelf of any sort. I wonder what would happen if I simply left everything out on the floor and spent the rest of my working days carefully stepping like a bespectacled giant over fragile glass jars of collected treasure and black ink pots with screw lids, weaving on a tiny scale between objects of usefulness and desire. Choosing to maintain forever the risk of losing paintbrushes and slivers of importance through the gaps between floorboards.

I will not do this, it is almost certain—to do so would possibly indicate that my wills to live were slipping, or that I’d surrendered too entirely to entropy, but the movement-induced throwing of my life and occupation into disorder has at very least reminded me to keep my verbs close, keep my treasures close, and to consequently keep saying aloud forever that everyone deserves that closeness.

n.b. There is a Companion Piece for No.225 going out to paid subscribers tomorrow afternoon, which continues the above

SUPPORTING THIS PLACE:

An offering of original drawings and a small selection of painted works (including the 100 Drawings Project) can be found in the usual place, that place being my website. If you’re interested in supporting The Sometimes Newsletter but do not wish to have a paying subscription then purchasing original work, or any of my books, also goes a long way to supporting—it also helps to ensure the regular, numbered newsletter remains available for everyone to read, and keeping the full archive (dating back almost eight years) open.

THIS WEEK I FELL IN LOVE WITH:

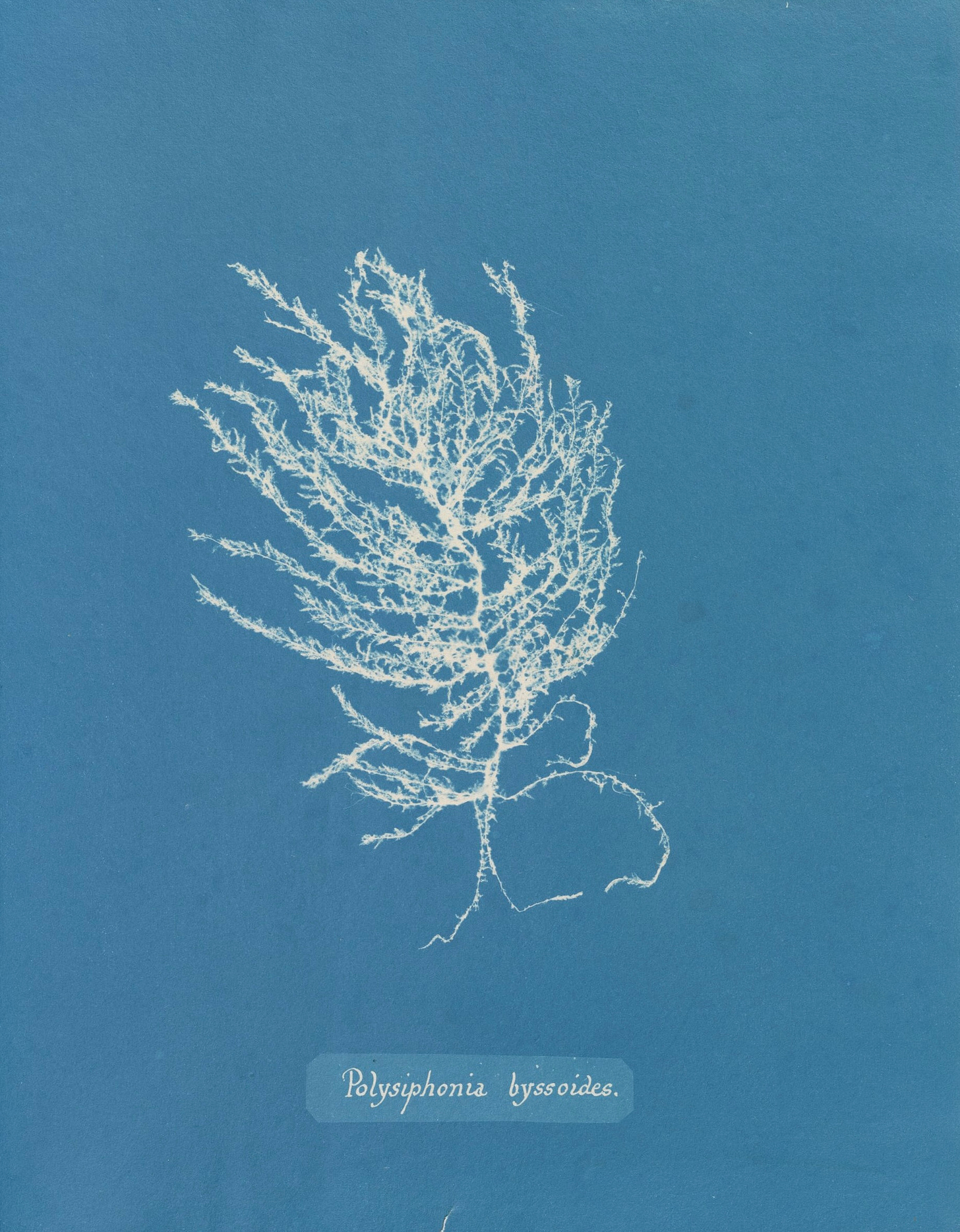

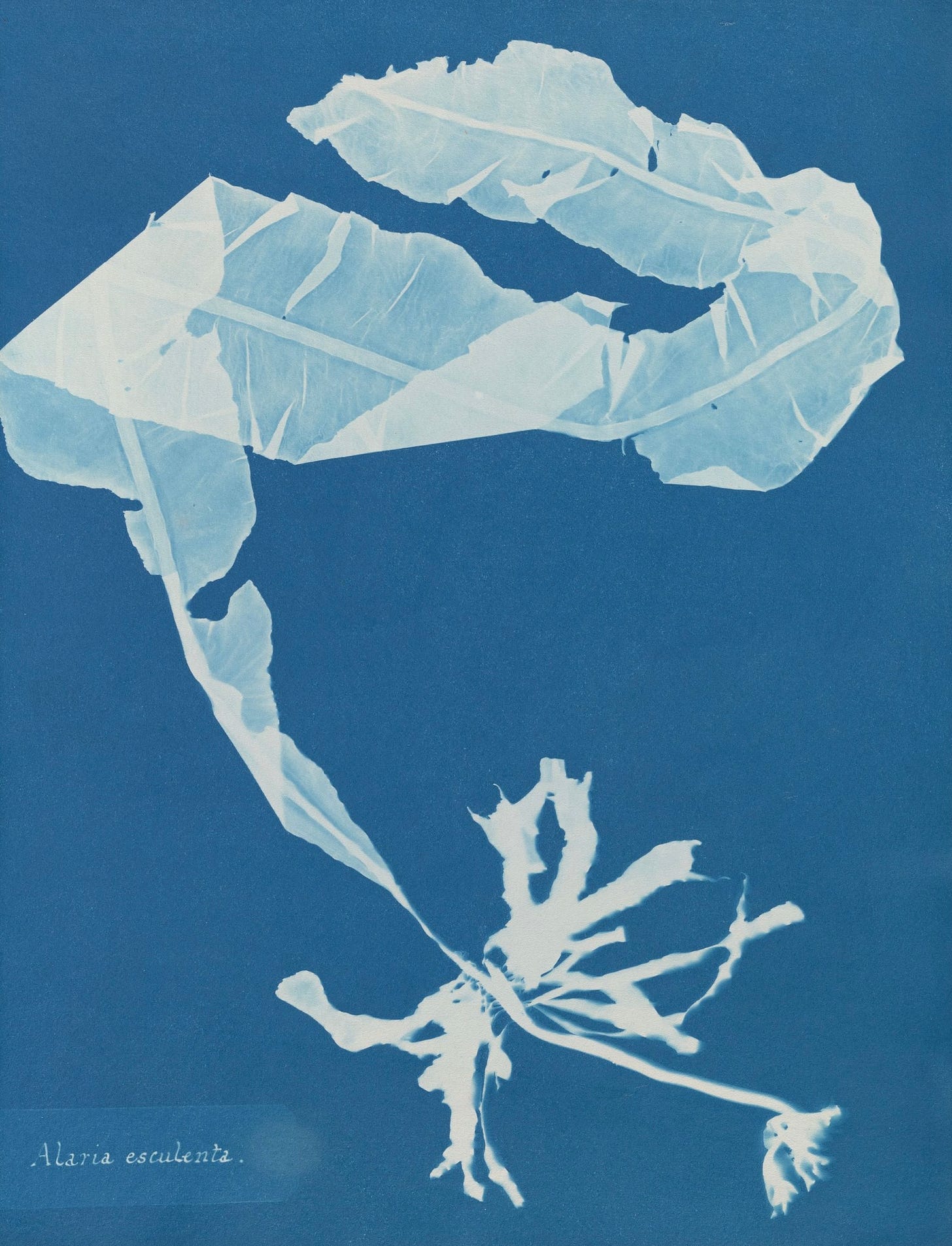

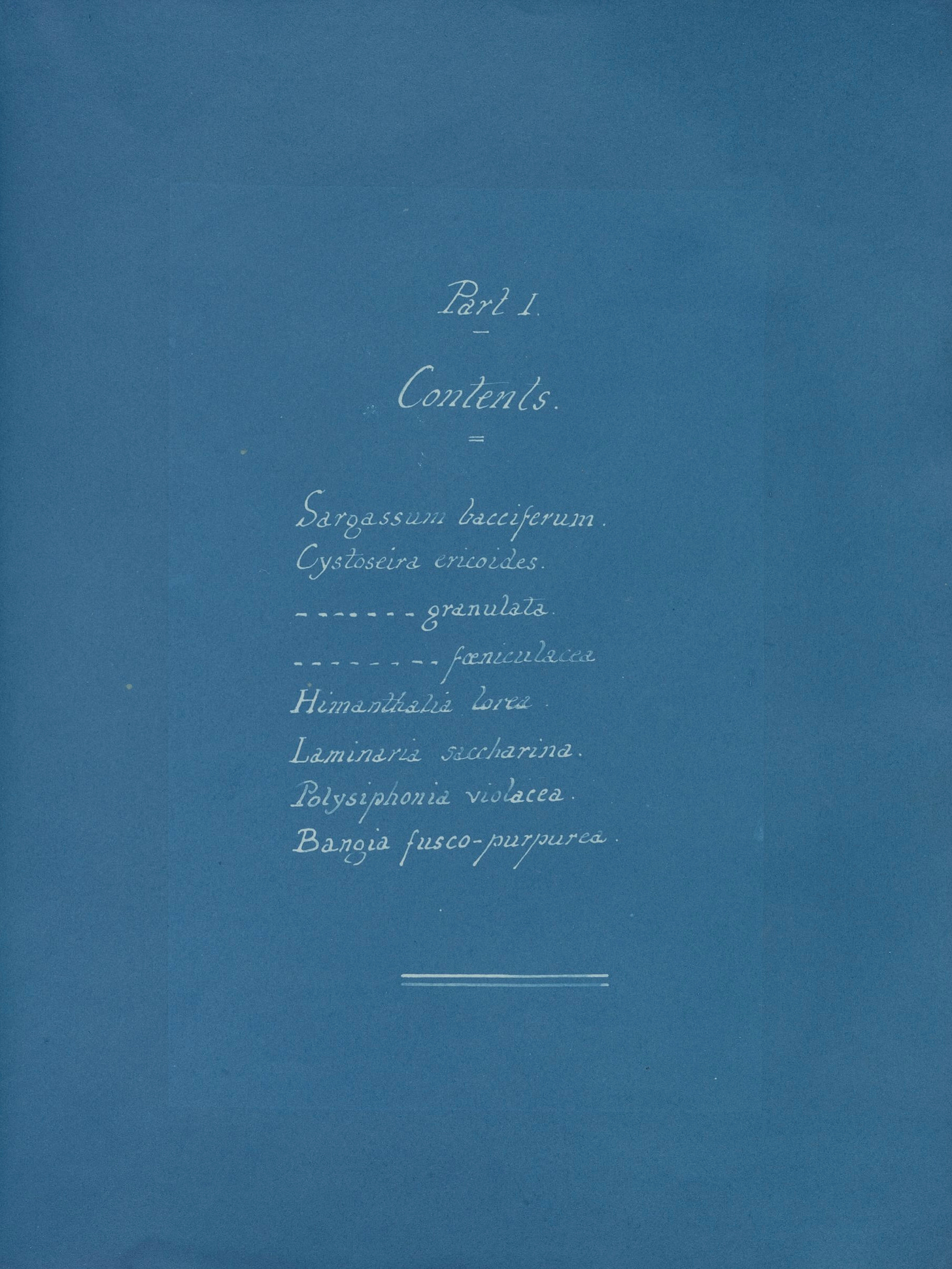

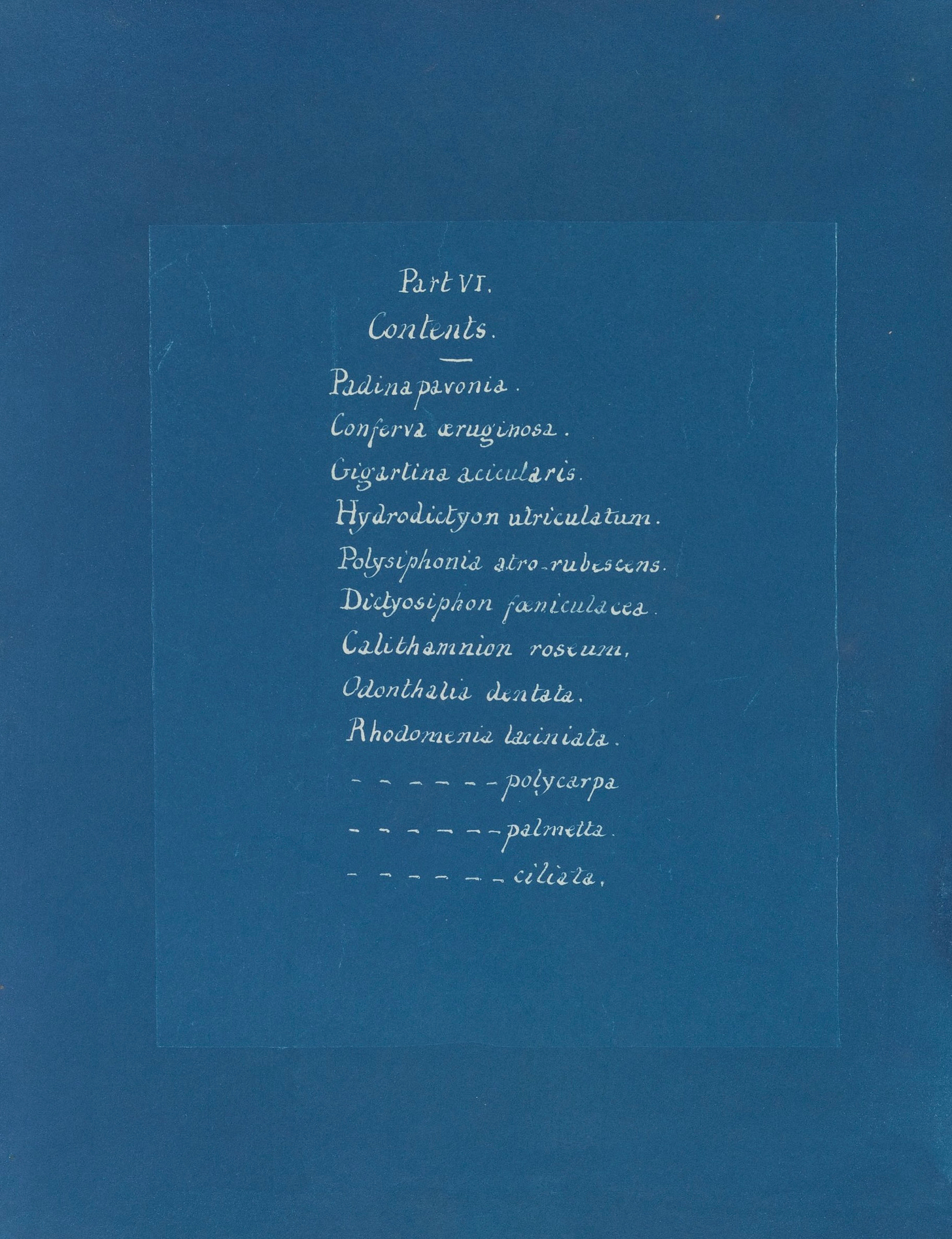

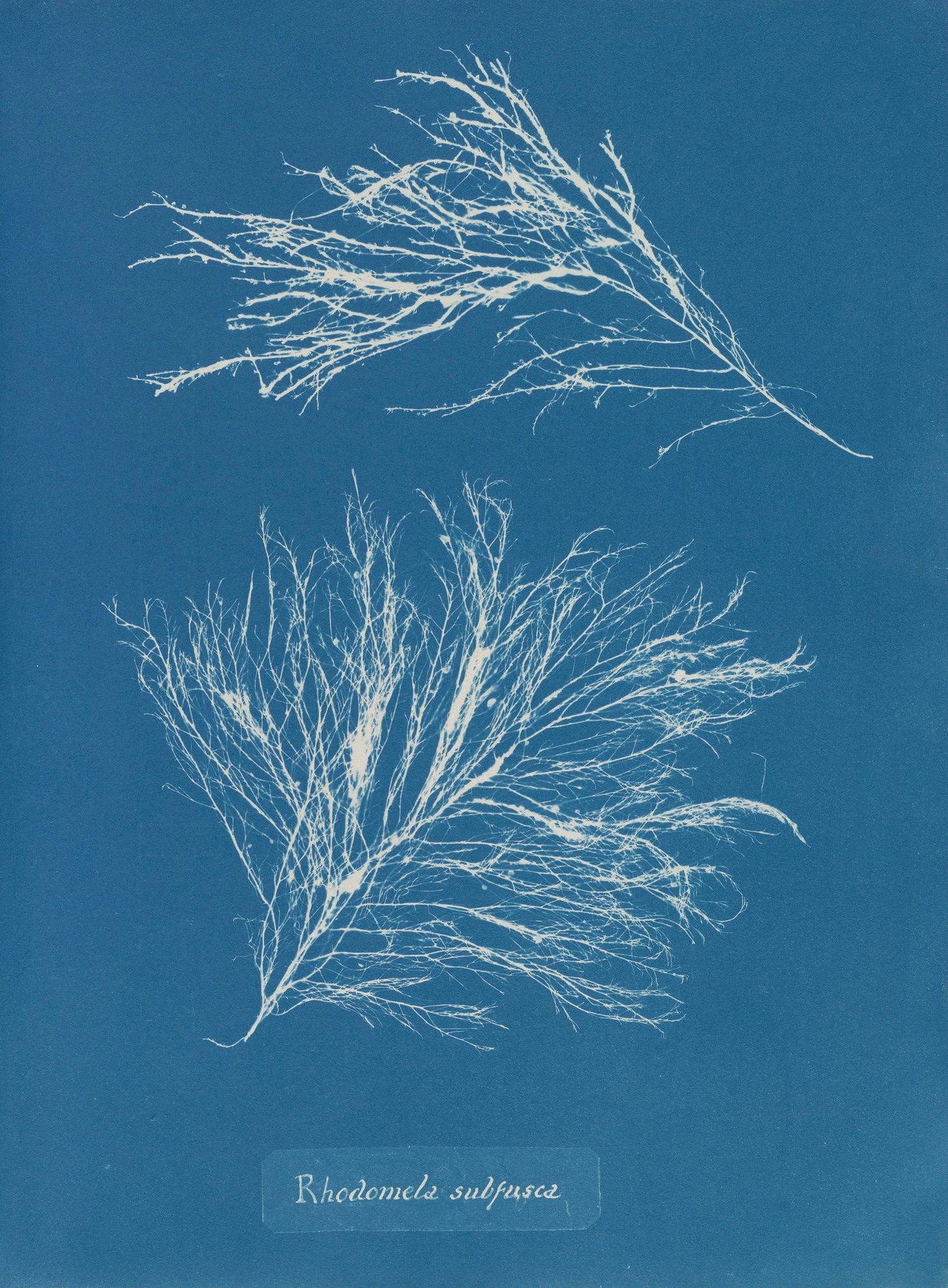

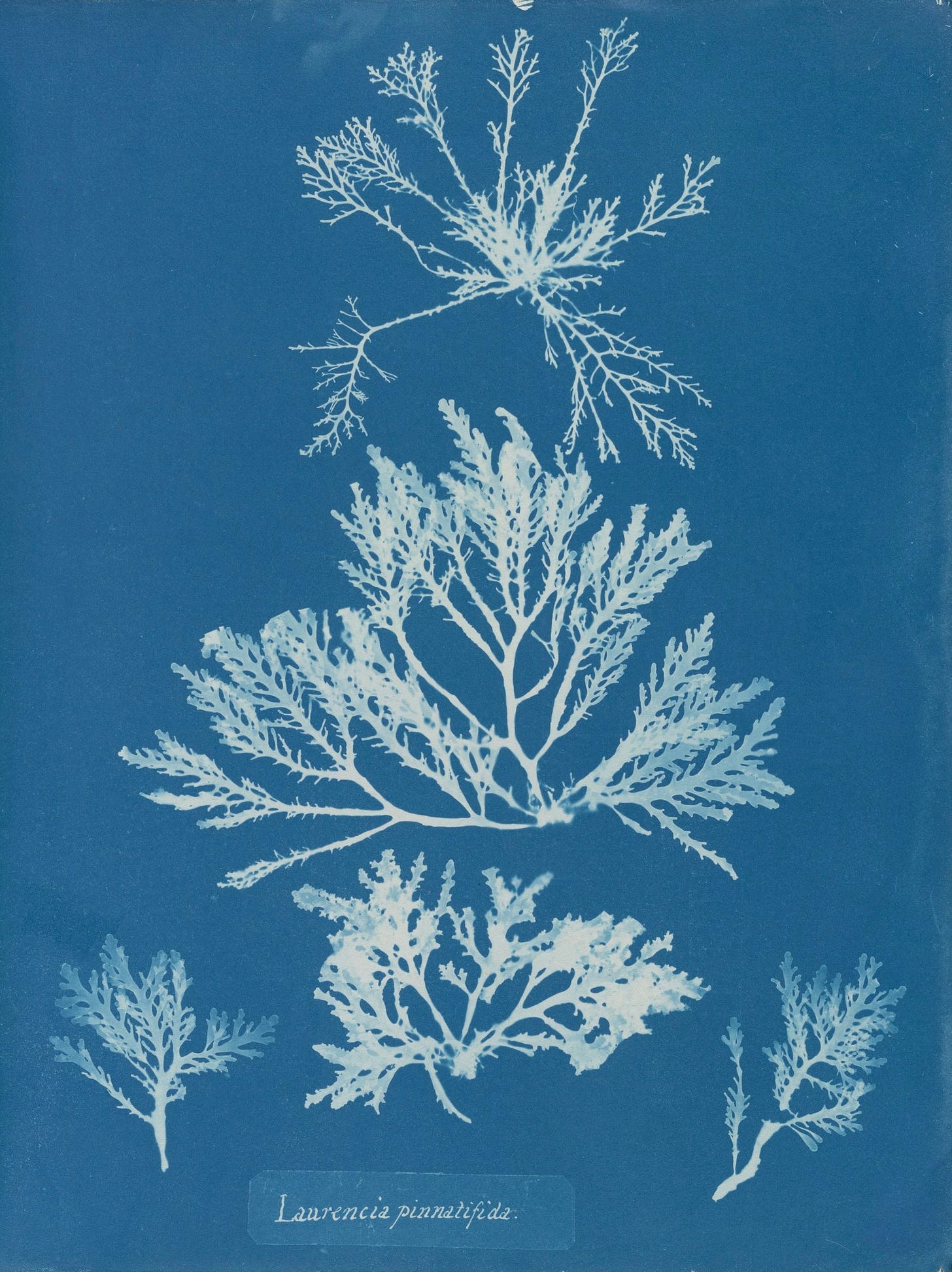

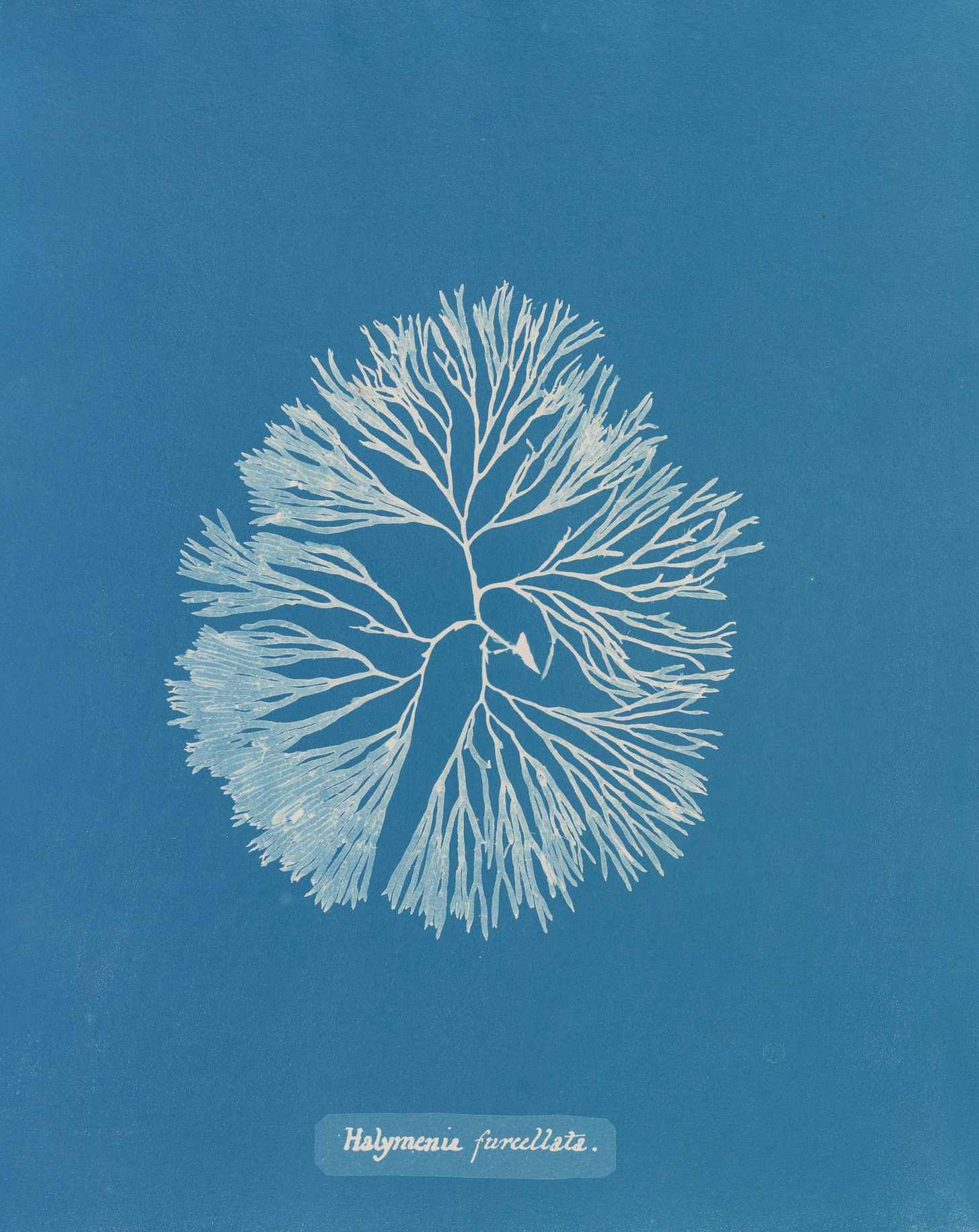

Shared by Freya Rohn in her intriguing ‘Commonplacing’ edition of The Ariadne Archive, these cyanotypes of various algae by amateur botanist Anna Atkins (1799-1871), which were created over the decade following 1843 and became the world’s first photography book: Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions. Freya mentions ‘Rhapsodies in Blue’—an essay published towards the end of last year about Anna Atkins and her work, which can be read on The Public Domain Review.

(The entirety of Atkins’ book is available to peruse on the New York Public Library’s Digital Collection.)

(I’m also quite in love with the hand-lettered Latin labels, the contents pages too, hence the inclusion of a couple of the latter.)

So many blues to contend with.

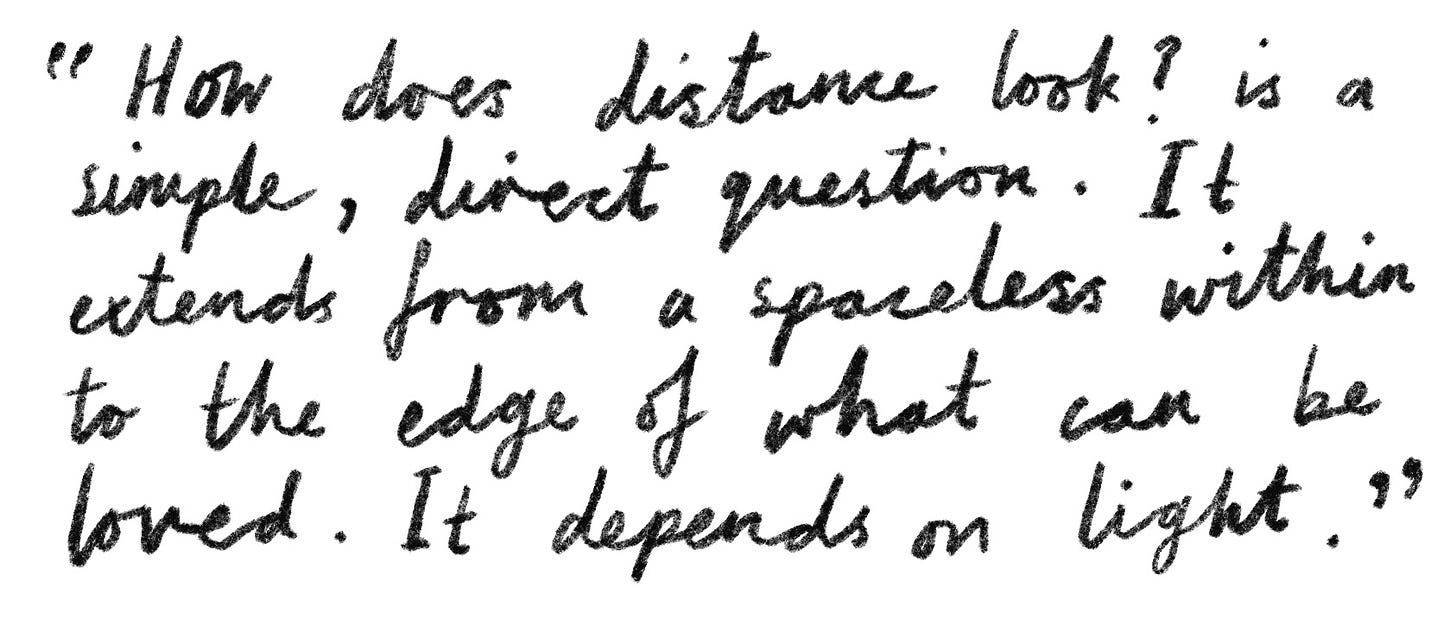

The suggestion of an ending is from a) Anne Carson’s Autobiography of Red:

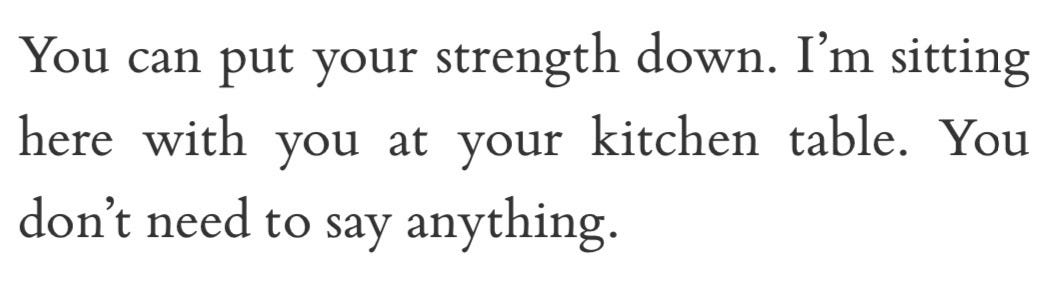

and b) Eden Robinson’s “Writing Prompts for the Broken-hearted”:

Which when added together form late afternoon light pooling on the wood of a kitchen table, of silences which hold far more than sentences spoken, of allowing yourself to sink into the eleven days of January which remain. When added together they make fingers cold but it doesn’t matter, a love stretched thin across distance and built from all the rules they tell you about light which never made any real sense anyway, and trying and trying and trying, then ceasing to try so hard.

"To think about the world and its ongoing pain is synonymous with needing ways to cope, and if one can find ways of coping then there is far more availability inside the nervous body to act." This, this, this.

Moved (unsurprisingly) to tears, Ella. Very little gives me courage and encouragement to hold on to hope in spite of the cruelties of the world the way your newsletter does. Thank you. Sending you much love.