No.211

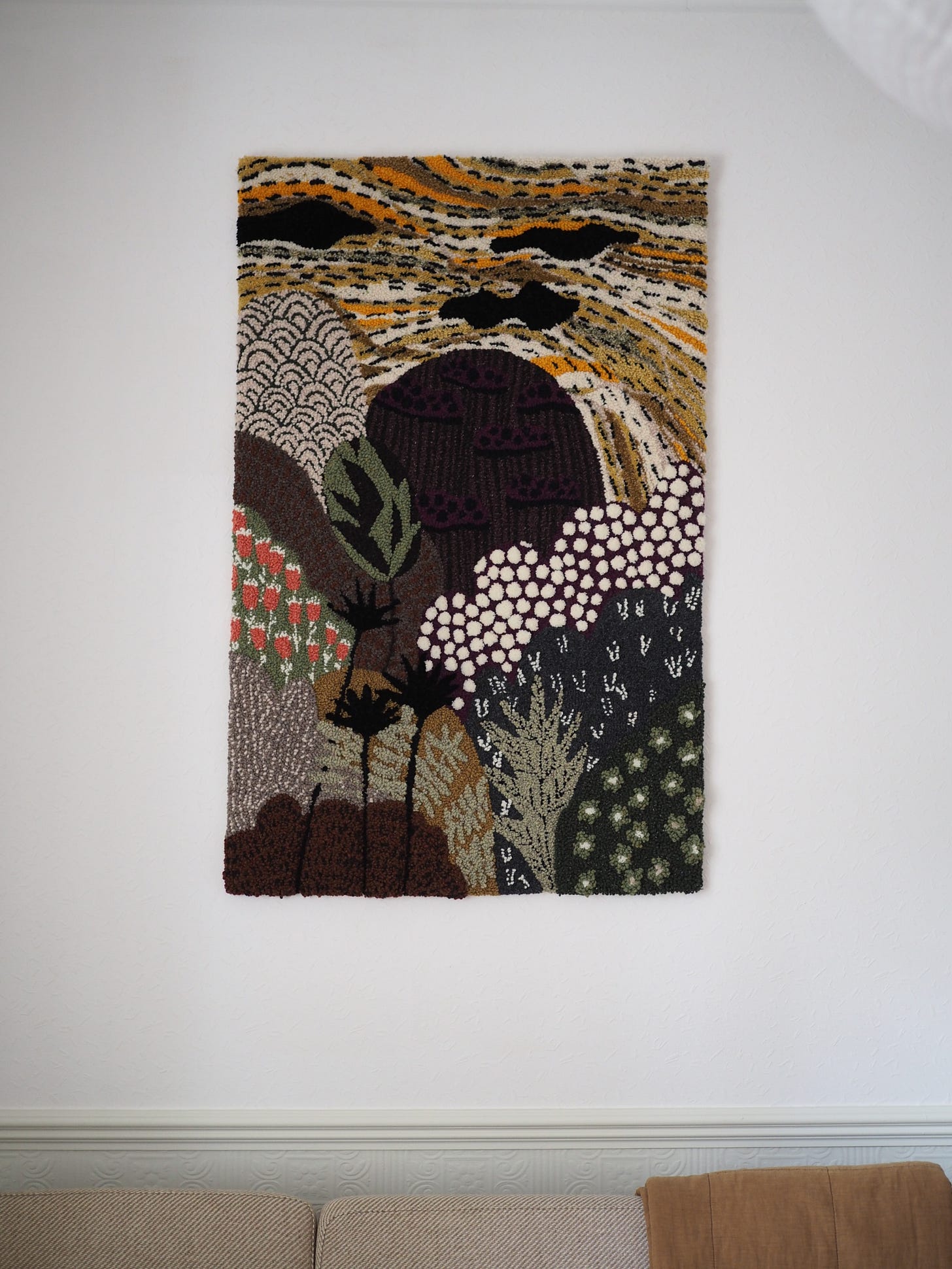

Soon enough it will be an entire year since the tapestry1 project was started, and I believe it’s taken two people ten or more months of intermittent work. As last year’s autumn unfolded into oranges and browns my partner suggested we adapt an illustration of mine to create a large (approximately 2.5 x 5 feet) wool wall hanging—I suppose because why not, and I suppose because the long Scottish winters lend themselves to unreasonable ambitions when it comes to attempts at maintaining one’s sanity during the absurd hours of non-sun.

The first chapter of Everything, Beautiful is called ‘How to Explain Beauty’, and the illustration selected for the wall hanging accompanies this initial part of explanation:

“I would like to explain beauty as something a bit like music, a bit like water, a bit like love.

I could explain beauty as things that cause you to stop, but also as things that cause you to begin. I could go as far as to say that beauty is the invisible‐visible force that makes things make sense, if only for a moment. I could explain it as the things that support the weight of our bodies. It might also be the reason why fish swim upstream, and the reason why we might choose to wake up next to the same person for sixty years.”

The design ended up needing to be reversed for the wall hanging, as we decided to work on the back towards the front side, rather than working solely from the front side, which then achieved a kind of intentionally varied, textural tufted effect, using punch needles at various lengths. It was like an ultra-endurance race for the arms, and looking at it now on the living room wall it seems like a kind of time monument—hundreds of coloured and concentrated hours fixed permanently into cotton cloth. It is impossible to make a tapestry quickly, it is definitely not one of the ways in which you can trick time.

Adapting illustrations from paper to wool is not something I’d ever thought of doing before, but the process lay somewhere in between meditative, ludicrous, and a magic trick, so I think doing more of these could be a consideration for the nearer future. There is a type of interaction with tapestry-like-things unlike those you can have with books, or artful objects, and possibly this is to do with the frequently large size, the fact that often you need to look up at them, craned, or maybe it is because of the time they hold onto and represent—in most ancient cases years, or even decades.

And—that the most intricate and ancient tapestries (in the true, warp and weft definition, like this, or this) are unsigned and to a large degree unknowable, because they were created primarily by women, and consequently we are never able to know whose lives were woven into those incomprehensible threads. There is a plain yet sharp-feeling mysteriousness to this.

What I’ve decided, after these months of painstakingly punching long and lunatic-feeling strands of wool into a piece of cotton monks cloth, is that slightly more of life might benefit from being mysterious, unsigned. I don’t mean this in a sense of not-knowing, or ignorance, or skirting around actual responsibility, but just leaning further into mystery, like stretching out your arms a little more in the dark, or like peering out beyond the routines we carve for ourselves in trying to maintain our illusions of safety.

One of the obvious things about mystery is that you cannot know exactly—or even at all—what will come out of it, and when so many aspects of life are entirely and forever uncertain or entropic it can feel uncomfortable to move very intentionally towards mysteriousness, towards secrets and questions and books that don’t immediately open. I suspect we need this though, a gentle move towards more mystery and less inherent assuming.

THIS WEEK I FELL IN LOVE WITH:

More images by Linda Brownlee, whose work I first fell in love with around the time of No.130, and who also was loved in No.202.

“Quite often I’m terribly disappointed by how things turn out, but that’s usually my own fault for the simple reason that I’m too quick to conclude that things have turned out as fully as it is possible for them to turn, when in fact, quite often, they are still on the turn and have some way to go until they have turned out completely.”

— Claire-Louise Bennett, Pond

And also, the people at the table across from me have a black dog called ‘Albus’; I know this because the woman keeps telling it to sit down Albus, settle down Albus, just sit down Albus, settle down.

The Sometimes Newsletter is a reader-supported publication, and if you enjoy reading the best ways you can support are to subscribe, share the newsletter with someone, or consider becoming a paid supporter.

The regular, numbered newsletter is currently still free for everyone to read, with paid supporters receiving several additional posts each month, including short stories, previously archived writings, and more detailed looks into creative processes.

I’ve learned that tapestry is technically defined as an image or design created by weaving coloured ‘weft’ threads through plain ‘warp’ threads