There be monsters, but not where you always expect. Sometimes the monsters are hiding in plain sight, or not even bothering to hide at all, not anymore, and I’ve gotten to thinking that this might be part of why a huge number of people—I’m supposing largely well-meaning people because the alternative doesn’t bear thinking about—have been openly supporting monsters, cheering for monsters, voting monsters into positions of absurd and undeserved and dangerous power. Hanging onto every word dripping from the monsters’ mouths and then repeating those words ad infinitum.

That is: we are often taught as children that monsters hide, or are hidden away and locked up for the safety of the realms, and so perhaps a great many people are stuck believing that monsters cannot be so monstrous if the monsters in question are photographed for magazine covers, given microphones and airtime and awards, quoted, and are rolling in billions upon billions of dollars.

“Then men loused everything up, driven by fear and envy (of women) and an unquenchable longing for organised sports … [they] have disastrously assumed the right to mess with the air, the water, the land, and our heads … They obliterate beavers so they can build their own dams!

War is the quickest way they’ve found to ruin the environment … People were apparently killing each other with arrows thirty thousand years ago, which is not nice, but outright group warfare only developed on a grand scale once metal weaponry was developed by Bronze Age societies, which were patriarchal … War devalues birth: that is its primary function. War is the rejection, demolition of women.” — Lucy Ellmann, Things Are Against Us

In the spirit of monsters I’ve been thinking lately too about work, as a word, as a pastime, as a seeming non-negotiable, as a trap, as a catch-all. The under of work and the over of it. Ellmann on overwork: [it] silences dissent and original thought and destroys physical, emotional, and community health. That’s what capitalists like so much about it.”

Also because the other day I wrote the word ‘work’ in a sentence but it came out as ‘worm’, and both share a page (302) within my Nuttall Dictionary of English Synonyms & Antonyms:

Work, v.a., Operate, exert, strain. v.n., Function, act, operate. Toil, drudge, slave. n., Toil, task, drudgery, labour, exertion. Production, product, fruit, results, issue, performance, effect. Book.

Worm, Wriggle, writhe, crawl, force, creep.

Immediately after worm on the page is worry.

“[there were days] when life appeared to her like a grotesque pandemonium and humanity like worms struggling blindly toward inevitable annihilation.” — Kate Chopin, The Awakening

We default to using ‘work’ when it comes to describing the vast and varied sea of different things people do, out of both need and choice, to ensure their survival on this planet. There are of course vocations and professions and callings and walks of life and trades, but all these are typically just pulled approximately together and simplified (conveniently for the cage of late-stage capitalism) as work. We go to work, or we don’t. We work hard or not enough, we dread going there and we look forward to its ending. We feel we have no alternative.

Someone has a double shift at a hospital? Work. Someone drives HGVs at night in the company of only streetlights? Work. Someone grows trees for other people? Work. Someone picks fruit in other languages and scorching temperatures? Work. Someone cares for other peoples’ infants? Work. Someone fixes car engines? Work. Someone films themselves reviewing other peoples’ books? Work. Someone films themselves renovating a house? Work. Someone squints through microscopes at bacteria? Work. Someone attempts to build a better world? Work. Someone stares into the toothy mouths of other people and probably sometimes the mouths of monsters? Work.

The word has connotations coming out of its ears, encompasses as many different experiences as there are people, and I think we’ve collectively forgotten (by design) that working 60-hour weeks it isn’t an inevitable thing but rather a desperate feature of societies crunching their consumerist numbers. Our individual and collective health suffers. Hugely. Not so long ago people might have worked for a handful of hours a day on the land, hours dictated not by dictators but instead seasons and weather and whether or not things grew well or poorly. Yes, this is a terribly simplified example and yes, different problems abounded, but the point is that it isn’t a immovable feature of the human experience on Earth to only, or mainly, work.

We are here to grow strong our bodies and grow wide our minds. We are here to notice when a seed first appears its tiny green hands out of the soil and to sit with our miracle arms around each other without regard for the minutes which could be passing. We are here to hold seriously the difficulties but not energetically fold ourselves into them, we are here to remain steady and expansive and sure-footed and true-mouthed because that is how all of this is going to continue towards something easier and something more deserving of the great cosmic unlikeliness of everything.

THIS WEEK I FELL IN LOVE WITH:

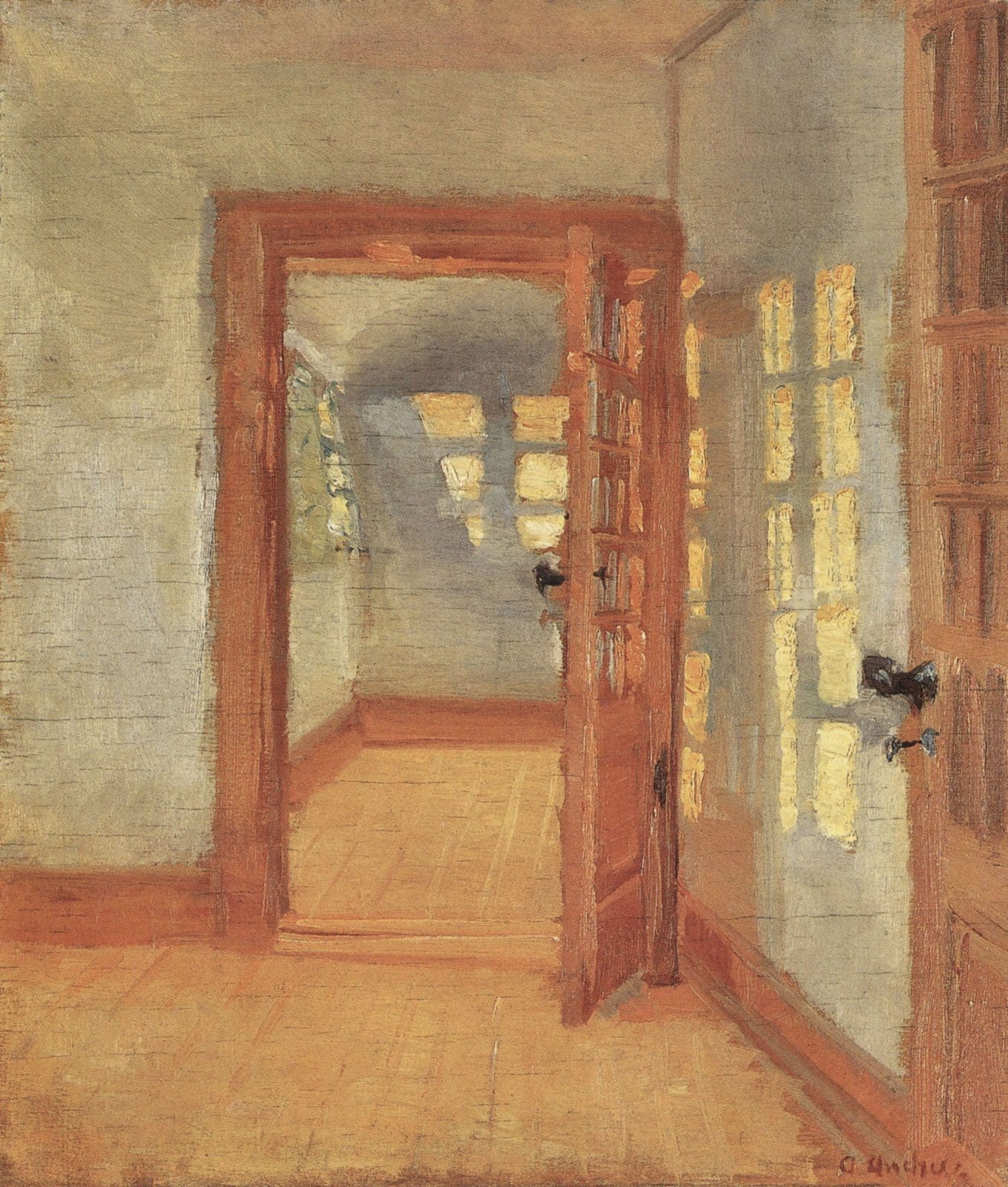

Women and interiors (women in interiors) within the works of Danish painter Anna Ancher (1859-1935). The initial photograph below is of Ancher in 1911, and the final painting is of Anna herself, reading, completed by her partner Michael Ancher in 1881 (‘The Artist’s Wife Reading’)—that lost, thoughtful slump of inside-a-book immediately recognisable.

Something not lost on me is the fact that many of her paintings have detail of filtered sunlight, patches of it segmented portioned up by windowframes, and plants, and a great, observed ordinariness.

Reading, currently, Arrangements in Blue by Amy Key, but only in short frustrated segments on the nights when I cannot fall asleep fast enough to escape the deluge of thoughts and feelings which I know fervently accompanies so many people now, before, always.

More than those late-night blue things though, which is feeling a bit trudging given the context of consumption: The Long Form (Kate Briggs) is still (somewhat bizarrely) very much on my mind well over a year after reading, due I think to its sheer unusualness, deceptive simplicity (far from simple), and, to me, vividly-but-unexpectedly affecting descriptions of an interior and exterior life, daily and essential happenings. I had lent the book to a family member and it was returned back to me recently, causing a fresh flooding of scenes and moments to return along with it. A park, flowers, a busy road, a man delivering a book and ringing the bell even though there was a note on the door saying do not ring, a baby crying, a mug placed in a houseplant to avoid getting up and waking the baby, and on and on. I think too though: Have I remembered anything of it at all?

“I have remembered, I suppose, what I wanted to remember; many ridiculous things for no reason that makes sense. That is the way we human creatures are made.” — Agatha Christie, Agatha Christie: An Autobiography

Again and for however long necessary: (Actions for demanding a Free Palestine and an end to occupation.) / (Reading list for a Free Palestine.) / (Postcards for Palestine, free PDF downloads.) / (Send a physical postcard.) / (Ten free ebooks for getting free from Haymarket Books.)

Paid supporters of The Sometimes Newsletter receive one or two additional pieces each month, including things like short stories, illustrated mini essays, and more detailed looks into creative processes. The most recent of these being:

Diminishing Powers

At some indiscernible moment during the last 480-plus days I ceased to be able to focus particularly well, and quite often the focus isn’t to be located at all. It turns out that even intermittent re…

Such a beautiful essay, Ella. Thank you.

Beautiful. So beautiful of a piece and in each element knitted together. I always look forward to your thoughts and those of others that you choose and the visual art you make and then choose. Thank you so much. The lift and poignancy this brings during this time is unmeasurable.