I’ve been thinking lately about windows. Thinking about what they stand for, what they say, what they try to keep in or out, what they can cause us to notice, what can be incorporated into our lives as a result of them.

The word used to refer to an unglazed hole in a roof which allowed wind to pass over, the Old Norse vindauga meaning ‘wind-eye’ (vindr meaning wind, auga meaning eye). Vindauga replaced the Old English eagþyrl, literally meaning ‘eye-hole’, and itself later replaced in most Germanic languages (Faroese and Norwegian still use a version of vindauga) by some variation of the Latin fenestra to mean a glazed, framed window, with English using fenester in parallel until the middle of the 16th century.

If windows started out as wind-eyes, as sky-eyes, then what is our relationship to them now? Do most of us still feel an ancient desire or compulsion to look out of them, or do we notice their framing of the exterior world less and less in favour of the digital ones that tend to grip our brains so tightly?

My initial hunch is that for almost everyone who looks at things using their eyes, if there is a window then it will be unfailingly looked out of. In biological-lizardy ways we like to be aware of our surroundings, alert, and I suspect this is why rooms and dwellings with a profusion of glass or openings in all directions can be alternately soothing and unsettling. Surely the brain always wishes to know what is approaching, and from all directions? There is a reason why people are punished and held in windowless places.

As our relationship to the outside has become—overall and generally and collectively—ever-more narrowed, progressively diluted in terms of ancient knowledge and our soft animal senses, perhaps the desire to look out of windows has in parallel become more urgent, unignorable. Looking out into a distance, whether that distance contains forested mountains or mountains of high-rise buildings, seems to me a perpetual small relief for any person. A wash, a cleansing, a start-from-the-beginning-again.

WORK-RELATED:

The spring issue of Orion magazine has already shipped out to subscribers, with the newsstand version on sale from the 11th, and inside can be found my usual Root Catalog column, this time pinned loosely to the Icelandic word víðsýni and its meaning of both a literal openness in the form of an expansive or panoramic view, and also of a liberal open-mindedness:

Sometimes when walking through the garden during the harshness of winter, I will mumble to the dormant trees and plants: Hang in there, keep going, the warmth will come back. Saying this as much to myself as anything else alive, but it helps, in the way that remembering people can and do change helps, in the way that reading about people replanting forests helps, in the way that seeing someone be completely who they are and have always been helps.

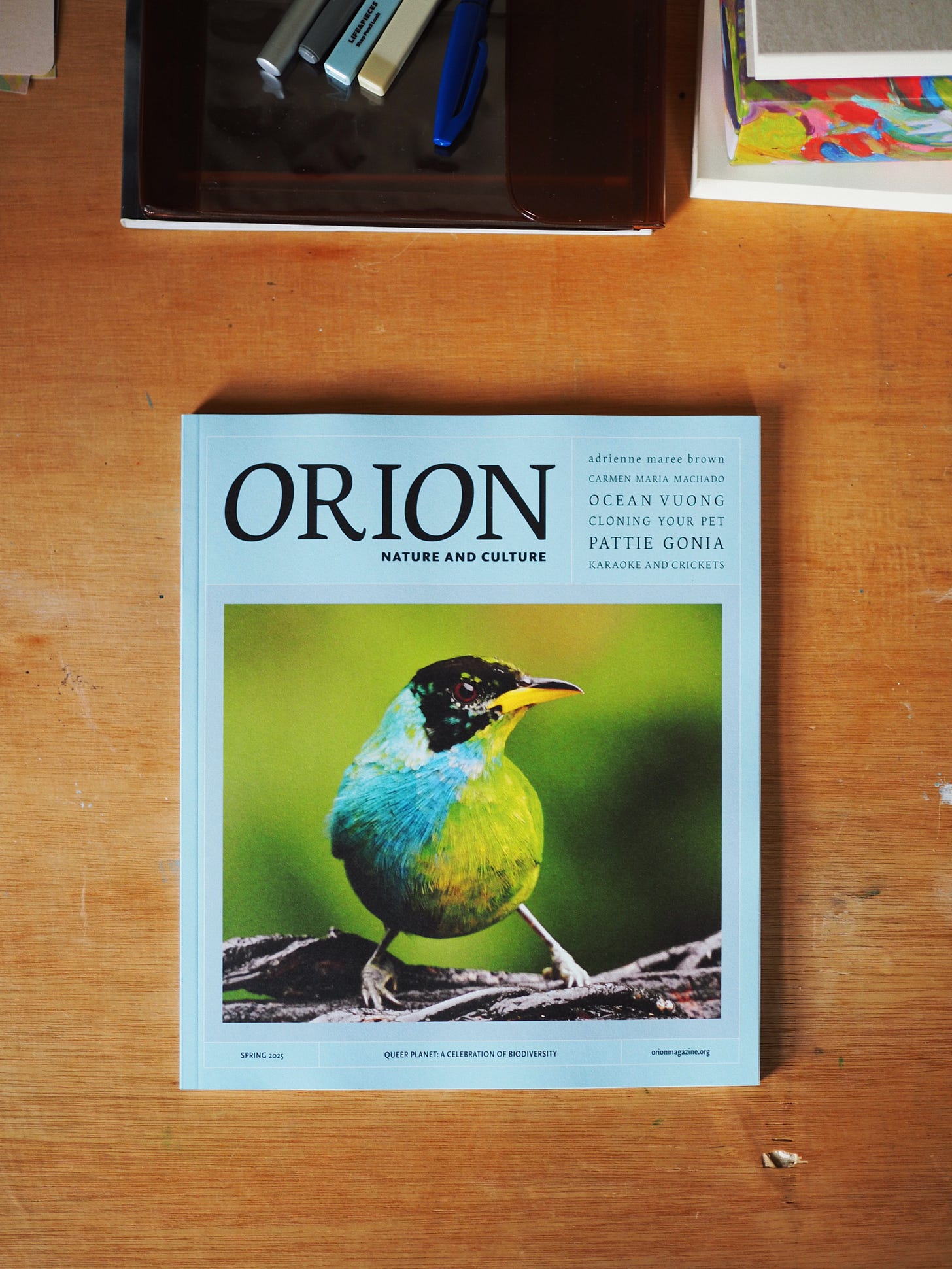

If you’ve been reading this sometimes newsletter for a while then you’ll perhaps recall that this issue—the magazine’s 200th—is also bringing with it a new visual, a redesign which, most bafflingly, I ended up being largely responsible for.

I’m honoured to be a part of Orion and all it stands for, all it offers out into the world, all it welcomes, and shepherding in a new design phase along with with a beautiful, compassionate group of people has restored to me more creative ooomph than I could have expected.

This spring volume celebrates the abundant queerness inherent in nature and its contributors shared their early copies with an excitement I’m overwhelmed to see—this along with Radiolab’s remarkable Lulu Miller having helped to oversee this 1.5-years-in-the-making project makes for a springtime offering that doesn’t get much more nourishing. Gift it to your people, your persons, yourself.

THIS WEEK I FELL IN LOVE WITH:

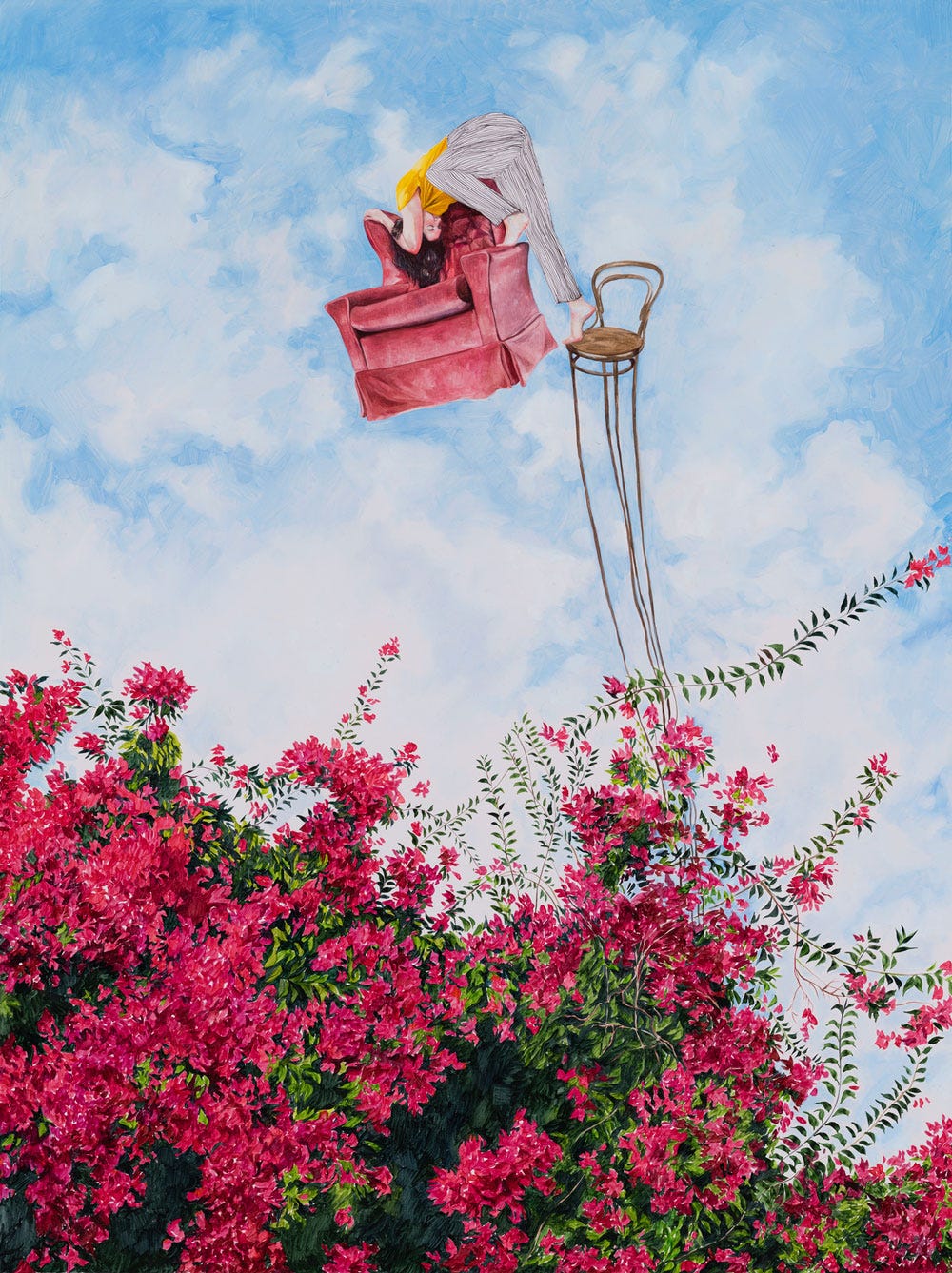

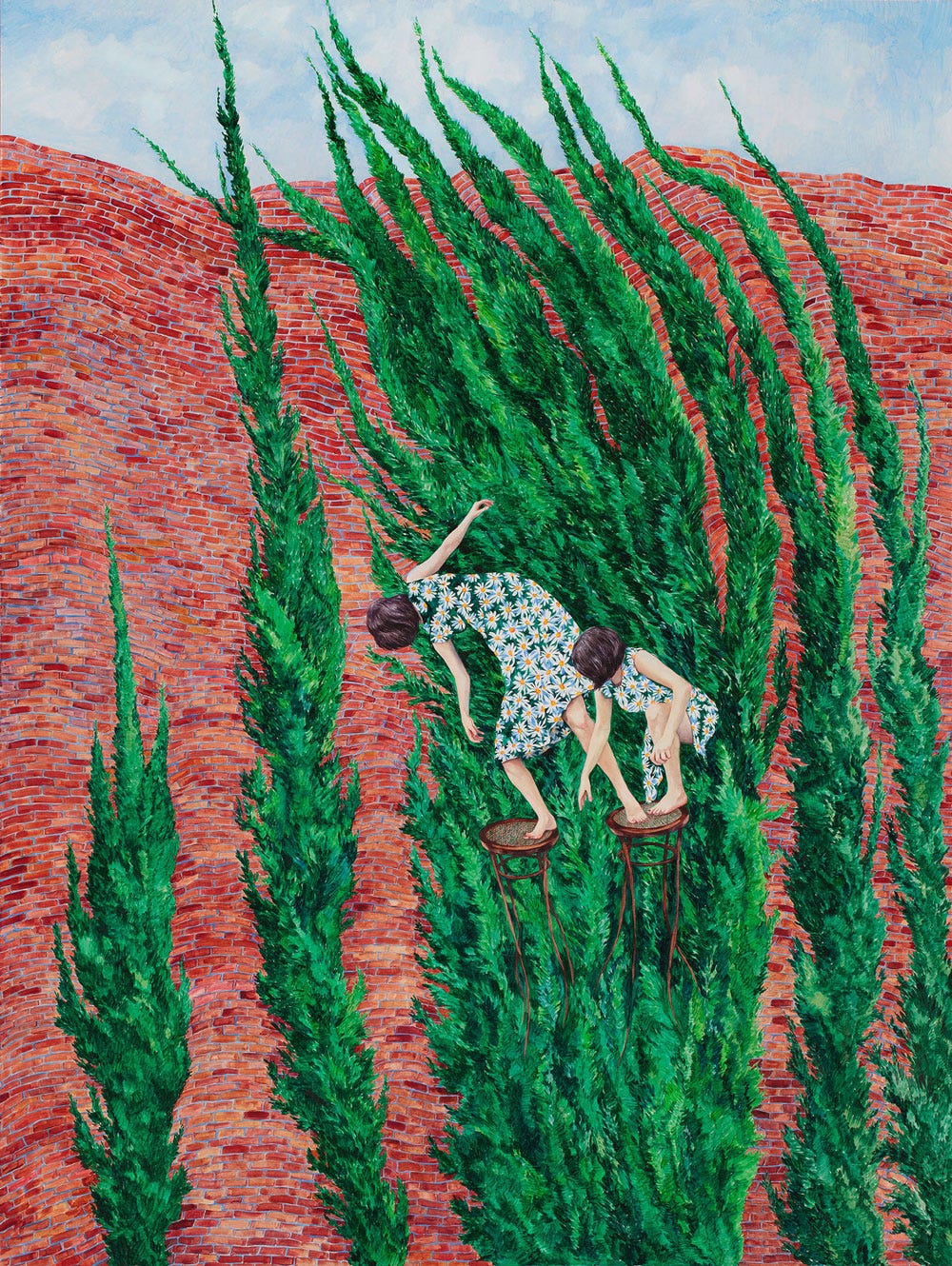

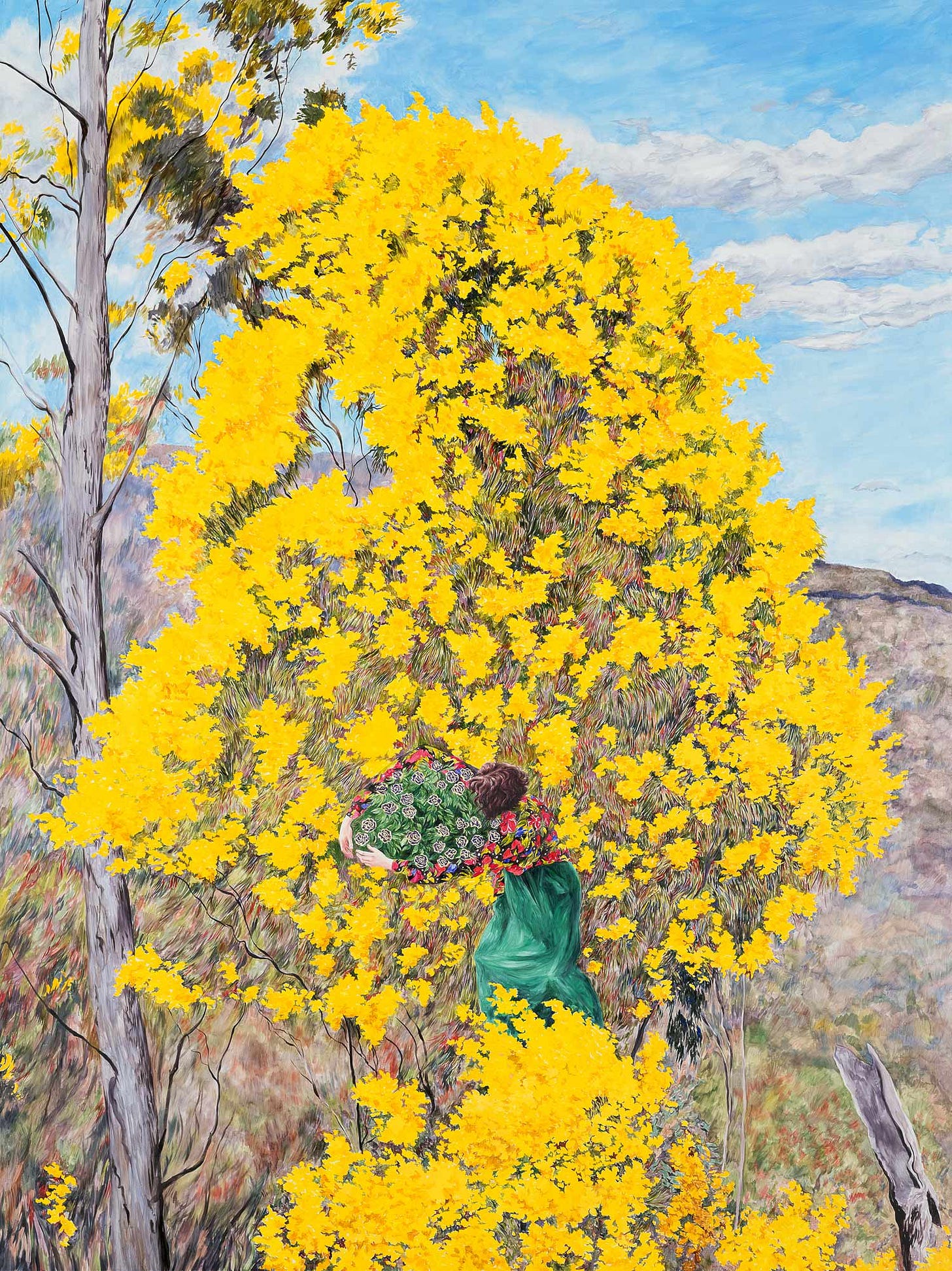

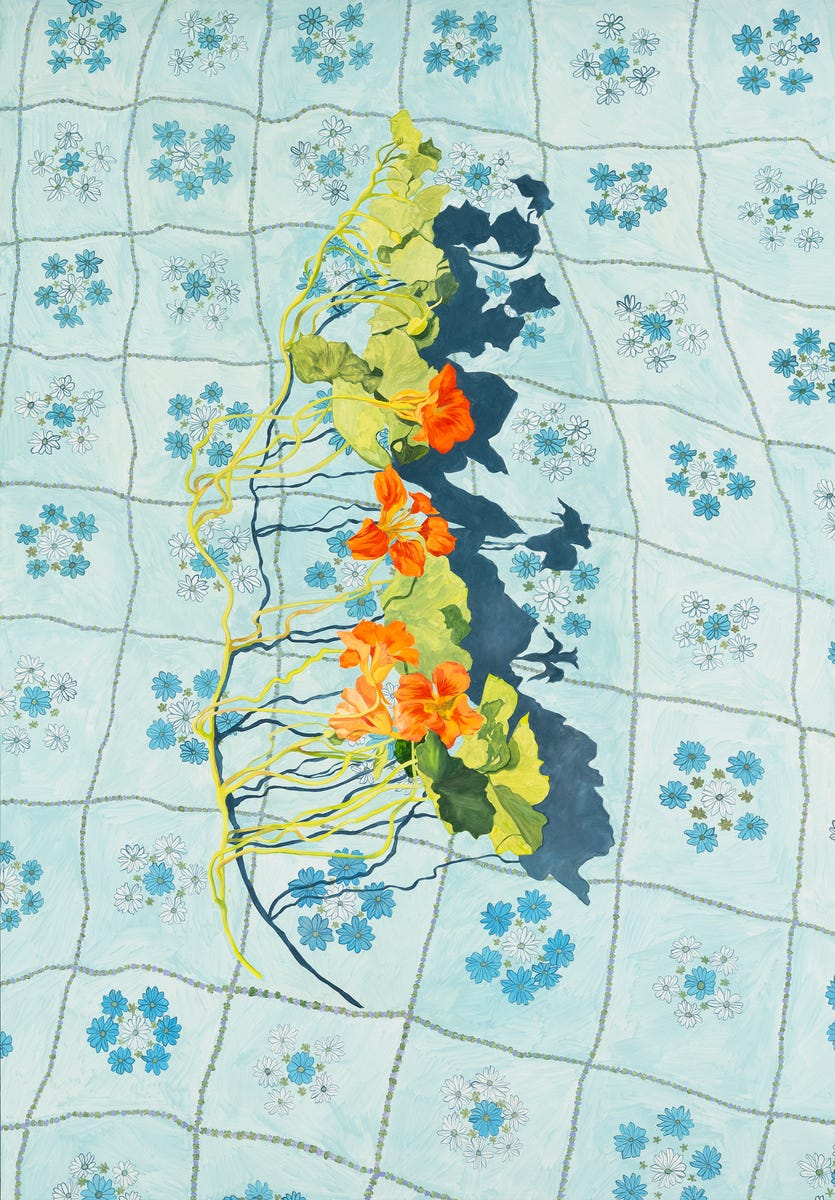

I don’t think it was love in this case exactly, but it was certainly a notable feeling of some indistinct sort towards these (to me) unnerving paintings involving Dalí-esque chair legs by Australian artist Monica Rohan, as well as some less unnerving watery-leaves. Something to do with how the present world-moment feels, how strugglesome or burdened the human shapes in these paintings appear.

After finding mention of it within an introduction to another Women’s Press book, I’ve started reading Kate Chopin’s The Awakening, which was vilified (along with its author) upon the original publication in 1899, needing until the 1970s for its themes to be appropriately appreciated and recognised. Most delightfully the book introduced me to the now-obselete word befurbelowed within the first fifty pages, to mean being ‘ornamented with frills’. Specifically the notion of being ‘freshly befurbelowed’ which I shall from this point forwards likely mutter to myself when having showered and dressed for the day. (Furbelow referring to a pleated or gathered piece of material, showy and somewhat superfluous.)

“It was strange and unfamiliar; it was a mood.”

Again and for however long necessary: (Actions for demanding a Free Palestine and an end to occupation.) / (Reading list for a Free Palestine.) / (Postcards for Palestine, free PDF downloads.) / (Send a physical postcard.) / (Ten free ebooks for getting free from Haymarket Books.)

Paid supporters of The Sometimes Newsletter receive one or two additional pieces each month, including things like short stories, illustrated mini essays, and more detailed looks into creative processes. The most recent of these being:

Diminishing Powers

At some indiscernible moment during the last 480-plus days I ceased to be able to focus particularly well, and quite often the focus isn’t to be located at all. It turns out that even intermittent re…